Class Notes: The Gilded Age

The late nineteenth century/early twentieth century is often referred to as "The Gilded Age," a term that comes from the title of a book written by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in 1873.

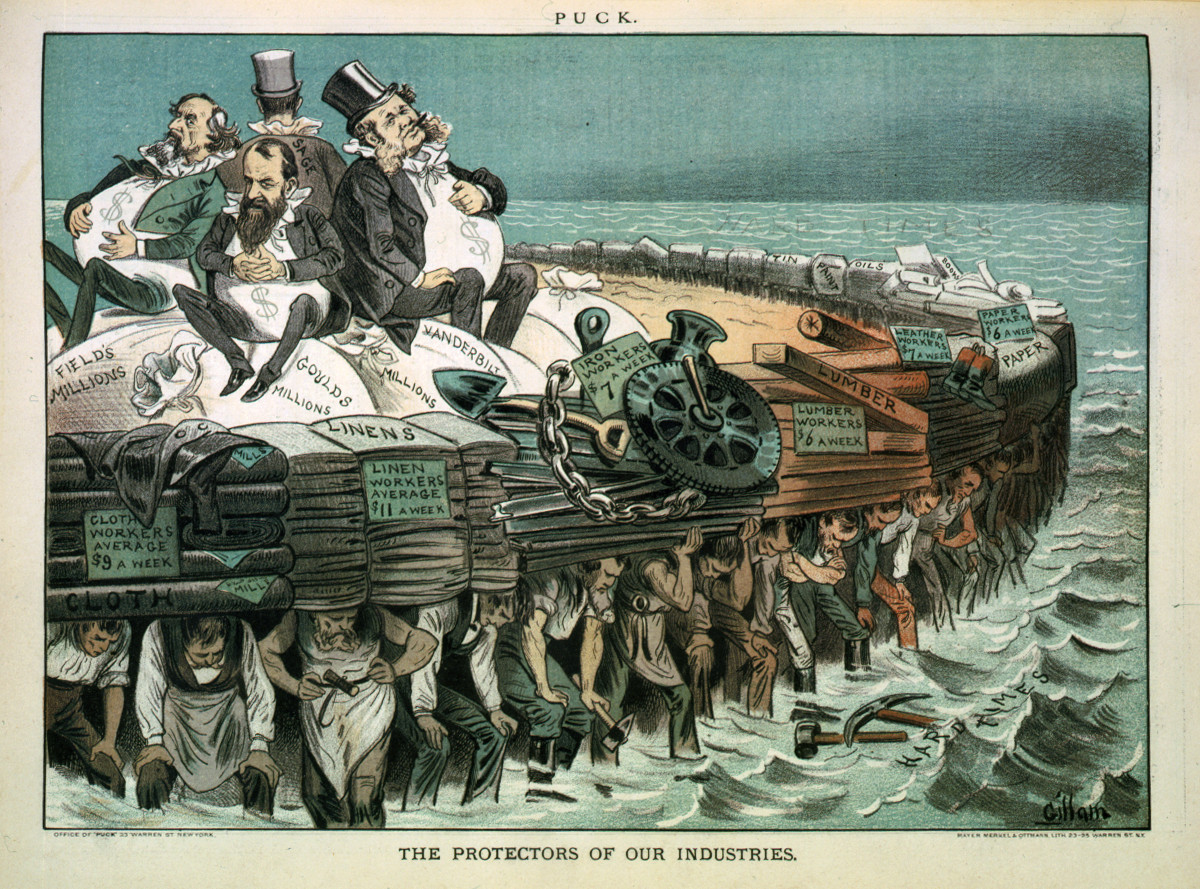

The Gilded Age satirized the excessive wealth and corruption of what we would call "the One Percent," but who in that day were referred to as the "Robber Barons." The "Robber Barons" included Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and a few other corporate titans (or captains of industry) who had built huge corporations and amassed enormous fortunes. Corrupt practices by these business tycoons, as well as by politicians, concerned many Americans.

The "Robber Barons" lived extravagantly. Pictured here are a few of their New York City properties (note that most owned multiple properties in the United States and even abroad; Carnegie's properties included a castle in Scotland and a home in Pittsburgh):

Andrew Carnegie's mansion, now the Cooper-Hewitt Museum

The Vanderbilt Mansion

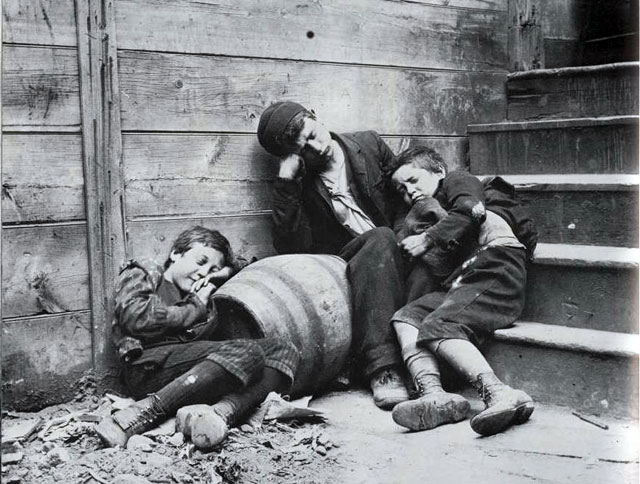

At the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum were the very poor, whose abject living conditions were detailed in the book How the Other Half Lives (1890), by Jacob Riis, a photojournalist and investigative reporter (known at that time as a "muckraker"). Riis called them "the other half," but they actually comprised about 75% of New York City's population. Many of the "new immigrants" lived in the "slums" (a new word, though not a new development in the 1890s) of New York City. Riis focused on the Five Points neighborhood on the Lower East Side, one of the most notorious New York City slums.

The wealthier classes justified their success and the poverty of the masses with the ideology of Social Darwinism, Charles Darwin's biological theory of the "survival of the fittest" applied socially, with the idea that the superior "race," the white Anglo-Saxon, rose to the top of society, while the "inferior races" (such as the "new immigrants" from southern and eastern European countries, many of whom had darker skin tones and were Catholic or Jewish) were inherently prone to poverty, crime, and other social disorders.

A strong nativist backlash emerged as the "new immigrants" poured into the United States and New York City in particular. Native-born white Anglo-Saxon Protestants began to associate the "new immigrants" with all of the problems of the new industrial America. Their large numbers, their differences (in appearance, religion, and social customs), and their poverty all contributed to a negative view of the "new immigrants" and reinforced the ideology of Social Darwinism. Francis Walker, a member of the Immigration Restriction League (founded in 1894 by a group of Boston elites) voiced this nativist sentiment in his calls for restricting immigration from southern and eastern Europe:

"The entrance into our political, social, and industrial life of such vast masses of peasantry, degraded below our utmost conceptions, is a matter which no intelligent patriot can look upon without the gravest apprehension and alarm . . . They are beaten men from beaten races; representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence . . . Their habits of life. . . are of the most revolting kind. Read the descriptions given by Mr. [Jacob] Riis of the police driving from the garbage dumps the miserable beings who try to burrow in those depths of unutterable filth and slime in order that they may eat and sleep there!"

In contrast, another group, the Progressive reformers, reacted differently. The plight of the poor and the socioeconomic inequities -- the vast gap between the living conditions of the "haves" and the "have-nots" -- concerned many reformers, who became part of the Progressive reform movement. The Progressive reformers especially focused on the problems of the new urban industrial America and its new immigrants, including housing and living conditions in slums and working conditions in factories.